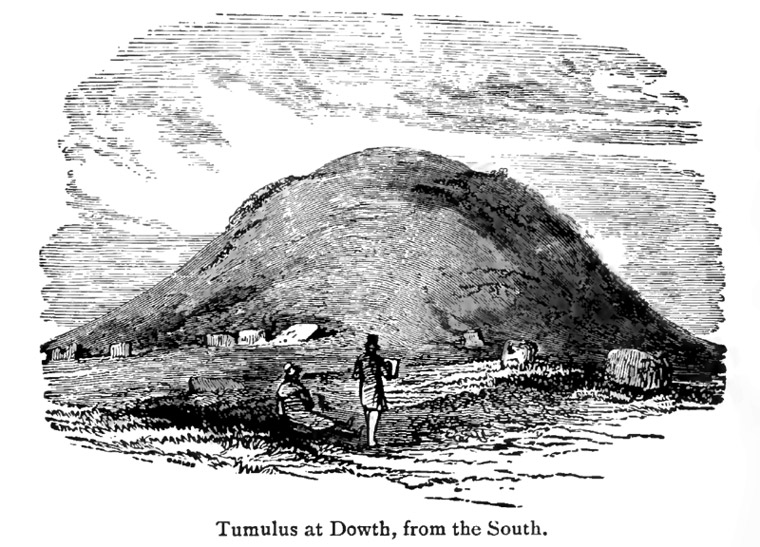

The Tumulus of Dowth

The Dowth

sepulchral mound corresponds closely to Newgrange in dimensions; it is about 47 feet high, and measures 280 feet

in diameter. Round the base is a belt of large stones as at Newgrange; but it has no retaining wall. A double circle

of stones appears to have surrounded the cairn. Of these the greater number lie buried; for in summertime

their position, particularly after a long continuance of sunny weather, is shown by the remarkably dry and

withered appearance of the grass above them.

The Dowth

sepulchral mound corresponds closely to Newgrange in dimensions; it is about 47 feet high, and measures 280 feet

in diameter. Round the base is a belt of large stones as at Newgrange; but it has no retaining wall. A double circle

of stones appears to have surrounded the cairn. Of these the greater number lie buried; for in summertime

their position, particularly after a long continuance of sunny weather, is shown by the remarkably dry and

withered appearance of the grass above them.

Of the internal arrangement of this great tumulus, little was known beyond the fact that it was different from that of the monument last described, inasmuch as, instead of one great gallery leading directly towards the centre of the pile, there appeared here the remains of two passages in a very ruinous state, and completely stopped up, neither of which, however, seemed to have conducted towards a grand central chamber. The Committee of Antiquities of the Royal Irish Academy having, in the course of the autumn of 1847, obtained permission from the trustees of the Netterville Charity, the proprietors of the Dowth estate, to explore the interior of the tumulus, the work was commenced and carried on at considerable cost, under the immediate direction of Mr. Frith, one of the county surveyors.

Unfortunately no official record of the work done has been kept, and the only account of it is a brief one by Sir Wm. Wilde. Commenting on this, Mr. George Coffey says: 'The mound was so pulled about by the explorers, and the work carried out with such doubtful wisdom, that the Committee seem to have had a not unnatural shrinking from publicity.' From the difficulty of sinking a shaft among the loose, dry stones of which this hill, like that of Newgrange, is entirely composed, the plan was adopted of making an open cutting from the base of the mound towards its centre, in order to arrive at the great central chamber which was supposed to exist. The first discovery was that of a cruciform chamber upon the western side, formed of stones of great size, every way similar to those at Newgrange, and exhibiting the same style of decoration.

A rude sarcophagus, bearing a striking resemblance to that belonging to the east recess at Newgrange, was found in the centre. It had been broken into several pieces, but the fragments were all recovered and placed together, so as to afford a perfect idea of the original form. In clearing away the rubbish with which the chamber was nearly filled, the workmen discovered a large quantity of the bones of animals in a half-burned state, mixed with small shells. A pin of bronze and two small knives of iron were also picked up.

With respect to instruments of iron being found in a monument of so early a date, we may observe that, in the Annals of Ulster, there occurs a record of this mound, as well as of several others in the neighbourhood, having been searched by the Northmen of Dublin as early as A.D. 862: 'On one occasion that the three kings, Amlaff, Imar, and Ainsle, were plundering the territory of Flann, the son of Coaing.' It is an interesting fact that the knives are similar in every respect to a number discovered, together with a quantity of other objects, in the bog of Lagore, near Dunshaughlin, and which there is reason to refer to a period between the ninth and the beginning of the eleventh centuries. Upon the chamber being cleared out, a passage 27 feet in length was discovered, the sides of which incline considerably, leading in a westerly direction towards the side of the mound, and composed, like the similar passage at Newgrange, of enormous stones placed edgeways, and covered in with large flags.

The chamber, though of inferior size to that of Newgrange, is constructed so nearly upon the same plan, that a description of the one might almost serve for that of the other. It is 9 feet by 7 feet and 11 feet high. There are three recesses between 5 and 6 feet deep; these, however, do not contain basins. The south recess leads into a double set of chambers, one extending south and the other west. A single stone 8 feet long forms the floor of the south passage, in the centre of which is a shallow oval 'apparently rubbed down with some rude tool.' A huge stone, in height 9 feet in breadth 8 feet, placed between the north and east recesses, is remarkable for the singular character of its carving. A portion of the work upon this stone bears a resemblance to Ogam writing.

Another sepulchral chamber, of a quadrangular form, portions of which show a great variety of carving, among which the cross, a symbol which neither in the old nor the new world can be considered as peculiar to Christianity, is conspicuous, has been discovered upon the southern side of the mound. Here, as elsewhere, during the course of excavation, the workmen unearthed vast quantities of bones, half-burned, many of which proved to be human; 'several unburned bones of horses, pigs, deer, and birds, portions of the heads of the short-horned variety of the ox, and the head of a fox.' They also found a star-shaped amulet of stone, a ring of jet, several beads, and some bones fashioned like pins.

Among the stones of the upper portion of the cairn were discovered a number of globular balls of stone, the size of small eggs, which Sir W. Wilde supposed probably to have been sling stones. Further excavations under the direction of the Board of Works (1885) led to other discoveries. An opening was made on the north side of the known entrance that 'led to a passage which terminated at either end by circular cells carefully roofed with corbelling stones'; and, where it met the entrance to the originally known chamber, a flight of steps was discovered. This and the character of the work, which is microlithic, indicate the portion of the underground passages and chambers to be a much later addition.

Among the trees between the mound of Dowth and the mansion are two smaller tumuli. One of these is open from the top; it contains a corbel-roofed chamber 10 feet in diameter and 8 feet high; round it are five cells constructed of small flags set upright. A little to the east of the house is a fine specimen of the ancient military encampment or rath, one of the largest in Ireland.

Tumulus at Knowth

The other great tumulus (Knowth) of the Boyne group has probably never been entered since the time, as the Annalists tell us, it was plundered and doubtlessly much injured by the Danes. It is nearly 7OO feet in circumference, and between 40 and 50 feet in height. For many years it has served as a convenient quarry for builders of houses and repairers of roads. That it could be explored at little cost is certain, as, owing to the denudation it has suffered, the passage or gallery leading to its chamber has, in part, been laid bare. Its circle or circles are not altogether obliterated ; and here and there some portions remain which show that the work, though less massive than that of Newgrange, was at least as striking as anything to be found in Dowth, or in connection with the remains at Loughcrew, or others occurring in the western districts of Ireland. Wakeman's handbook of Irish antiquities

is a comprehensive guide to the rich history and culture of Ireland. Written by prolific author and writer William Frederick Wakeman,

this classic book is a must-have for anyone interested in the ancient and medieval heritage of the Emerald Isle.

Wakeman's handbook of Irish antiquities

is a comprehensive guide to the rich history and culture of Ireland. Written by prolific author and writer William Frederick Wakeman,

this classic book is a must-have for anyone interested in the ancient and medieval heritage of the Emerald Isle.

The handbook covers a wide range of topics, including prehistoric monuments, ancient burial sites, medieval churches, castles, and monastic settlements. Wakeman provides detailed descriptions and explanations of each site, drawing on his extensive knowledge of Irish archaeology and history. What sets this book apart is Wakeman's engaging writing style and his ability to bring the past to life. He delves into the myths and legends surrounding the sites, providing fascinating insights into the beliefs and traditions of the ancient Irish people.

Whether you are planning a trip to Ireland or simply want to delve into its rich history from the comfort of your armchair, Wakeman's handbook of Irish antiquities is an invaluable resource. It is a timeless classic that will continue to inspire and educate readers for generations to come.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Visitor Centre

| Tours

| Winter Solstice

| Solstice Lottery

| Images

| Local Area

| News

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Articles

| Art

| Books

| Directions

| Accommodation

| Contact