Inside the Neolithic Mind

Inside

the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods by David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce.

Inside

the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods by David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce.

An exploration of how brain structure and cultural content interacted in the Neolithic period 10,000 years ago to produce unique life patterns and belief systems. What do the headless figures found in the famous paintings at Çatalhöyük in Turkey have in common with the interlinked spirals carved on the monumental tombs at Newgrange and Knowth in Ireland? How can the concepts of "birth," "death," and "wild" cast light on the changes in relationships between people and animals?

David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce examine the intricate web of belief, myth, and society in the Neolithic period, arguably the most significant turning point in human history, when agriculture became a way of life and the fractious society that we know today was born.

The authors focus on two contrasting times and places: the beginnings in the Near East, with its cult buildings and skull burials, and western Europe, with its massive stone monuments. They argue that neurological patterns hardwired into the brain help explain the nature of the art, religion, and society that Neolithic people produced. Drawing on the latest research, the authors skillfully link material on human consciousness.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Excerpt from Chapter 8 - Brú na Bóinne

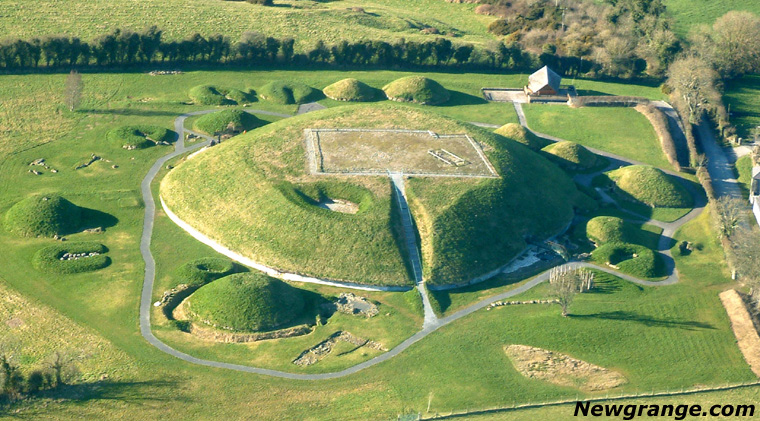

When viewed northeastwards from Rosnaree, the Bend of the Boyne rises like an island surmounted by, from west to east, the Knowth, Newgrange and Dowth ridges. Each of the three large tombs, Knowth, Newgrange and Dowth, has small satellite passage tombs and is on the summit of one of these ridges; they are intervisible. There are also standing stones, a cursus (processional way) and a number of henges within the Bend.Although it may not point unequivocally to strife, archaeological evidence shows that an early passage tomb, probably the first of the great Bend of the Boyne structures, was dismantled. At least 15 decorated stones from it were used in two subsequent tombs, Knowth and Newgrange, the principal foci of this chapter. The motifs carved on the stones from the old monument are rectilinear, whereas those in the two more recent tombs are contrastingly curvilinear. Moreover, the re-used stones were placed so that their decorated surfaces were, apart from one exception, either wholly or partially obscured; some that became orthostats were inverted, decorated portions going into dug sockets.

It is, of course, possible that the earlier tomb was amicably dismantled to make space for the large Knowth tomb that we see today, but the ways in which the 'borrowed' stones were used suggests that there was some estrangement between the early tomb people and the builders of the second. Exactly what the dispute was about no one knows. Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that such a major change in religious practice (dismantling a passage tomb and building another as a new ritual centre) could be accomplished without a certain amount of debate and friction between groups of people. A state of affairs of this kind may account for both continuity and change. Another passage tomb, similar in overall shape and structure, though much more impressive and requiring a great deal of labour, was built. There was thus some continuity. But parts of the old one were incorporated in ways that downgraded their status. The motifs on these stones retained some of their 'power' (they were not obliterated), but their influence was diminished. This subordination probably paralleled a decline in the influence of those who controlled the old tomb.

Another point worth noting is that the highly decorated kerb around the large Knowth mound (somewhat later than the tomb) suggests a public face intended to be seen and perhaps processed around by many people, whereas the inner sanctum would be visited by the few. It is all very well to see such a distinction as being between, on the one hand, the general populace and, on the other, loved and respected elders whose every word is a beatific revelation. It seems more likely that distinctions of that kind would be, at least intermittently, contested. As Marx and Engels dramatically proclaimed (not without reason),'The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."

The notion of endemic Neolithic conflict is not new. In a seminal article, Colin Renfrew saw developments in the Wiltshire Neolithic as the result of competition between growing chiefdoms or polities. Julian Thomas and Alasdair Whittle have put forward a similar explanation for changes in the use of the West Kennet long barrow (chambered passage tomb) in Wiltshire. They write about 'heightened competition', a 'progressively more restricted segment of society', 'continued group differentiation in the area' and, from our present point of view most aptly, 'the closing down of a redundant monument, redolent with powerful associations and which offered competition to new traditions'." In Denmark, too, changing Neolithic burial practices have been interpreted as negotiation of social relations rather than an attempt at a prehistoric revolution. The events at Knowth are also comparable to those that led to the building of the Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb on a henge, though in Anglesey the new structure seems to have reflected a resurgence of old beliefs and power.

No different from any other society, Neolithic political and religious groups were probably conflictual rather than consensual. But this strife was not automatic and impersonal: groups do not act blindly, without leaders who are fully aware of what they are doing. With parallels frequently evident in present-day societies, the past was, in Julian Thomas's phrase, 'manipulated and recreated in order to support social change'. Neolithic leaders manipulated the social contracts of the time, and, as their focus on tombs and religion shows, associated consciousness contracts as well. The political influence and range of the Bend of the Boyne and the monumental elements within it waxed and eventually waned.

These brief remarks provide a background against which we can view the astounding concentration of Neolithic achievement within the Bend of the Boyne.

A moated grange

Viewed from the tombs, the Boyne forms a semicircular 'moat'. Just to the north of the loop, a smaller river, the Mattock, flows west-east to a confluence with the Boyne at the eastern end of the Bend. A point that does not seem to receive sufficient attention is that virtually all the Neolithic monuments of the immediate area are within this two-river moat. No significant Neolithic monuments are known on the immediate southern side of the river. To the north of the Mattock, near Townleyhall, is a single passage tomb. Within the northern part of the Bend (as defined by both the Boyne and the Mattock) is a 'ritual pond' south of Monknewton. It is on the isthmus leading into the Bend. Probably dating from the Late Neolithic, it comprises a 2m (6.6ft) high bank enclosing a 30m (98.4ft) in-diameter area that is filled with water. Close by is an earthen enclosure.Clearly, the loop of water was, in some way, significant to Neolithic people: it 'contained' a major ritual centre. Probably, the symbolism of water and rivers that we discussed in connection with henges was operating here as well, though on a larger scale and with the added factor that the Boyne provides an easy route to the sea. Water thus demarcated an 'Isle of the Dead' and linked it to the great water, the sea. We have here another suggestion of death (carrying the dead to the tombs) entailing crossing a river and of the realm of the dead being associated with the sea or, more conceptually, a place 'under water'. Ideas of this kind contribute to an explanation of why Neolithic people sometimes disposed of the dead in rivers

Within the Bend, Neolithic people constructed a range of monuments in an efflorescence of activity paralleled in only a few other places in western Europe. In addition to the great megalithic passage tombs with their high, covering mounds, there are many smaller mounds and tombs, earth enclosures, timber circles, stone circles, pit circles and a cursus. Religious experience and belief, set within complex social parameters, together with what we can call early scientific observation of the heavens, produced a repeatedly resculpted landscape dominated by massive, commanding structures that are visible from afar and - it is hard to avoid the conclusion -proclaimed political power built on a religious foundation. As we have already seen, Rousseau said: 'No state has ever been founded without Religion serving as its base.

We have argued that spatial divisions in Near Eastern buildings were symbolic of experiential, social and cosmological distinctions. In western Europe, people went further. Not only did individual monuments, such as tombs and henges, relate to cosmology. The people also mapped cosmology and its social and religious implications on to extensive tracts of land. In the great west European centres of Neolithic activity the conceptual cosmos came down to earth in ways that still amaze those who walk over a terrain that was, in those times, a map, or replica, of the people's evolving conception of the whole universe and their place within it. Walk along the great avenue of standing stones that leads to the Avebury henge in Wiltshire, or up the sloping, earth-banked avenue that leads from a shallow valley to the heelstone that marks one's arrival at the (until that dramatic moment) hidden Stonehenge. You will begin to appreciate, though perhaps not understand, the vastness and subtlety, ingenuity and technical brilliance, socio-political labyrinth and conceptual intricacy of the Neolithic world - and, above all, of the drama of Neolithic landscapes. You will realize why Neolithic monuments have had such an impact on Western thinking and art.

Before the tombs

Prior to the Neolithic, during Mesolithic times, the Bend of the Boyne was heavily forested. The rich environment with its animal and aquatic life afforded the hunter-gatherers of the time a comfortable living. Today the stone tools of this period turn up in ploughed fields: arrowheads, burins, scrapers and artefacts apparently used for making holes in leather. Although archaeologists who have systematically walked across fields have found concentrations of stone artefacts, they have not been able to locate any indisputable Mesolithic settlements within the Bend. Nor is there any sign of religious practices.There is more evidence for Early Neolithic activity. The remains of timber houses from this period were preserved under the later tomb mounds. They have been dated to between 3900 BC and 3500 BC. Nine of the houses were circular, perhaps a pre-echo of the great circular tombs to come. Studies of these and other Irish Neolithic houses have suggested that the nature of settlement varied during the period. At some times there was more mobility than at others, and there was also a tendency for houses to cluster together. Towards the end of the Early Neolithic, there are indications of social differentiation within settlement sites.

The date of the earliest Bend of the Boyne Neolithic settlement (3900-3500 BC) should be compared with the earliest evidence for farming in Ireland as a whole, which points to a date of about 4200 BC, or perhaps a few centuries later. Whether they were immigrants or local Mesolithic communities of hunter-gatherers, the first Neolithic people settled in Ireland in clusters of houses; they practised mixed farming - cereals, cattle and sheep, all of which were imported from Europe and, of course, ultimately from the Near East. The artefacts of these pioneering communities suggest some continuity with Mesolithic life-ways, though the break is distinct: the Neolithic was indeed 'new', though not an invasion, not a full-scale population replacement. One can say that the Neolithic 'arrived' here, whether as a group of people, a package of life-ways or, as now seems more likely, piecemeal, whereas it 'developed' much more slowly in the Near East.

Gradually or not, the west European Neolithic impacted heavily on the environment. We saw that in some Near Eastern localities, early farming led to soil erosion; in the west. Early Neolithic people began to clear the forests and thus to change and mould the landscape - a process that continued into the later period of the passage tombs and mounds. Indeed, forest destruction continued through to, and after, Elizabethan times. At the same time, the people moulded the landscape conceptually, giving meaning to special locations.

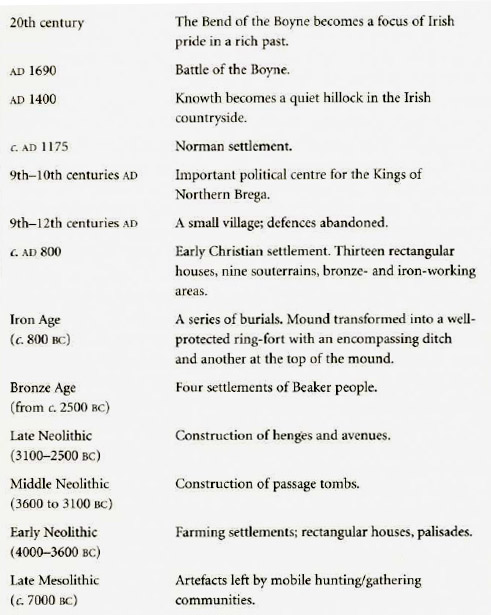

The extensive human settlement in the Bend of the Boyne that forest clearance permitted was of long duration. It extended from those early houses through periods of massive tomb-building in the Middle and Late Neolithic down to 2500 BC and beyond. What we see today is a pile of semi-transparent pages, the texts of each superimposed on and partly obliterating earlier pages. Disentangled, the evidence suggests the general progression shown in the following table:

A full discussion of every monument in the Bend of the Boyne is not our aim. Instead, we focus on two tombs: Knowth and, the most famous of all Irish passage tombs, Newgrange. Our focus on these two monuments takes us on from the previous chapter by casting further light on what happened in and around Neolithic tombs. It also develops two themes at which we have so far barely hinted, but that tell us much about Neolithic religious belief and practice: the importance of stone as a substance and the power of carved motifs to integrate architecture and religious experience.

Reviews

'Bold, provocative, scintillating, a brilliant synthesis of archaeology and human neurology. The authors break new ground and give one food for thought on every page' - Professor Brian Fagan'An engaging, well-written and erudite book, which makes many suggestive observations and provides stimulating reading' - British Archaeology

'An adventure in the archaeology of religion, of wide interest to the professional world and perhaps of even wider interest among general readers'- Choice

'Gives us as clear a picture as I've seen of how the people of the New Stone Age thought, of the myths that sustained them and of what they really believed' - The Sunday Telegraph

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Visitor Centre

| Tours

| Winter Solstice

| Solstice Lottery

| Images

| Local Area

| News

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Articles

| Art

| Books

| Directions

| Accommodation

| Contact