Knowth | Fifty years of excavations

Six millennia of ritual and settlement : Helena King, Royal Irish Academy 2012

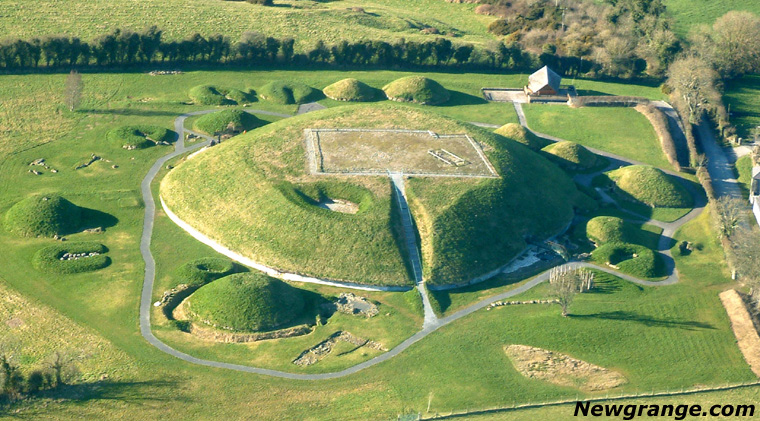

Aerial view of the Knowth site | Large mound (known as Knowth Site 1) and smaller satellite mounds

On June 18th 1962, George Eogan and a team consisting of four general operatives and six students began excavating a passage tomb at Knowth, Co. Meath. 'Little did I or they know that it was the start of a marvellous journey of archaeological discovery, excitement, hard work and the start of a great many friendships, both professional and personal.' These were Professor Eogan's words on 20 June 2012, when he and more than 200 others were back at Knowth to reflect on what the intervening half-century had wrought. The occasion marked the 50th anniversary of the programme of excavations at Knowth, celebrating the work of all those involved in the excavations and related research over the years, and also the launch of The archaeology of Knowth in the first and second millennia AD, the fifth volume to date in the Royal Irish Academy's series of monographs bringing the findings from those excavations to publication.

In 1962, the then Dr. Eogan was attached to the Department of Irish Archaeology at Trinity College Dublin, which was headed by Professor G.F. Mitchell. Eogan had previously excavated an unusual passage tomb at nearby Fourknocks, and Professor Mitchell suggested that the site at Knowth may be worth investigating to see what further light might be shed on the passage tomb archaeology of the area. At that time, all that was visible was a large, grass-covered mound, roughly 30ft high and covering an acre of ground.

John Rock and George Eogan at the opening to the passage of the Eastern tomb at Knowth in August 1969

Now, after many years of excavation, analysis and conservation, the site at Knowth has been revealed to consist of not only that large Neolithic-era mound, which unusually houses two passage tombs beneath it, but also 20 smaller satellite passage tombs, a protected double-ditched enclosure constructed in the seventh/eighth century AD and in use as such until perhaps the tenth century, and an enclosed courtyard farm from the Middle Ages. In the seventeenth century, a settlement cluster emerged to the east of the main mound, along the line of the public road, and later again, a farmhouse and associated buildings and features evolved on the far side of the road. This farm remained in operation until the 1960s, when the buildings were acquired by the Irish state. The main tumulus site had been in state hands as a national monument since 1939.

In 1987, the Boyne Valley Archaeological Park was established, incorporating Knowth, Newgrange and Dowth; in 1993, the entire area was designated by UNESCO as the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Site. The Brú na Bóinne interpretative visitor centre, built and run under the auspices of the Office of Public Works, was opened in 1997 near Donore, Co. Meath, on the south side of the River Boyne. The OPW has overall responsibility for the site at Knowth, which is open to the public seven days a week from April to October, with access managed via the visitor centre.

The Neolithic passage tombs at Knowth date back to approximately 3,500BC. The site is older than the Egyptian pyramids; older than Stonehenge. Overall, Knowth has had a history, though not continuous, of ritual and settlement spanning roughly six-thousand years from the beginning of the Neolithic to the modern era. The Knowth tomb builders were skilled craftsmen. They constructed two passage tombs beneath the main mound; each of which had a large burial chamber. Professor Eogan and his teams of trowellers rediscovered the western passage tomb on 11 July 1967; this passage tomb is approximately 34m long and ends in an undifferentiated chamber that was segmented by two sillstones. Just over a year later, on 1 August 1968, an even more dramatic discovery was made.

A second, larger tomb (its passage just over 40m long) lay back-to back with the western tomb. This eastern passage tomb ended in a cruciform chamber with a magnificent corbelled roof, and there was a carved stone basin containing cremated remains in the right-hand (northern) recess of the chamber. Unlike Newgrange's single tomb chamber, which is lit by the rays of the dawning winter solstice sun, the twin chambers of the main tomb at Knowth are not as precisely aligned astronomically. The eastern tomb faces generally towards the rising sun at the spring and autumn equinoxes, and the western tomb faces the setting sun at the around the same time.

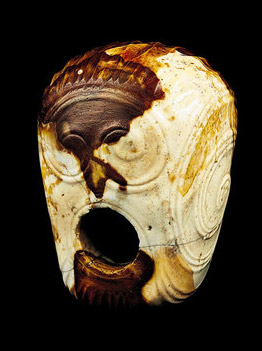

Knowth may not have Newgrange's astronomical precision, a reason, perhaps, why it is not as well-known in the general cultural consciousness beyond the archaeological community as its sister site along the Bend of the Boyne. What Knowth does have, however, is an extraordinary collection of megalithic art. The orthostats lining the passageways to the eastern and western tombs feature a variety of carved symbols. One of these orthostats near the chamber of the western tomb is etched with an anthropomorphic figure with two large eyes, perhaps a stone guardian protecting the remains of a prestigious member of the Neolithic community for whom the burial ground was constructed? Around the exterior of the large tomb are enormous carved kerbstones with a variety of abstract motifs.

Each of the 20 smaller satellite tombs also feature carved megalithic art. In fact, Knowth and the other passage tombs in the Boyne Valley contain the largest collection of megalithic art in Europe. Reason enough for Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht Jimmy Deenihan, TD, to describe the Brú na Bóinne passage tomb complexes as 'the jewel in the crown of our cultural heritage', as he did at the celebrations at Knowth but there is even more to Knowth.

In George Eogan's words, Knowth is a 'multi-period and multi-cultural site first occupied by the earliest farmers who lived in this area close to six-thousand years ago'. He has categorised the various stages of settlement and habitation at Knowth into twelve cultural phases. The best known is undoubtedly the passage tomb phase, but another remarkable stage of Knowth's evolution extended over the seventh to twelfth centuries AD. In the seventh/eighth century, the main passage tomb mound was transformed into a double-ditched enclosure, a development that marked the first major structural alteration to the site since the original construction of the passage tombs.

Although there is clear evidence for Beaker-related activity at Knowth in the beginning of the Bronze Age (c.2300BC), throughout the remainder of the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age human activity at Knowth and the wider Brú na Bóinne area is limited. During the Late Iron Age, from approximately 100BC to roughly AD300, the site was used for burial, with the remains placed in simple pit graves without formal protection in various places around the main tumulus (among the grave goods discovered in these Late Iron Age burials were blue glass beads; the number of such beads retrieved at Knowth is more than twice the combined total from all other Irish Late Iron Age burial sites). Burials dating to the seventh to ninth centuries were recovered around the main tomb mound and in the passages and chambers of several of the smaller tombs also.

The construction of the double-ditched enclosure, according to Eogan, marks the emergence of Knowth as an important royal residence for the kings of North Brega. It may never be possible to determine exactly why Knowth was chosen as a new political centre by the North Brega branch of the Síl nÁedo Sláine dynasty (part of the southern Uí Néill) that controlled this region, but the mound of the main tumulus occupied a prominent and commanding location, offering wide-ranging visibility of the surrounding landscape.

The archaeological evidence suggests that the ditched settlement fell out of use at the end of the eighth or during the course of the ninth century AD, and was replaced by an open-area settlement, which continued in use through the tenth and eleventh centuries up to the beginning of the twelfth. This was a time when the North Brega kingdom was particularly influential. The mound of the main tomb continued to function as the core area of the settlement, and there was limited habitation on the adjoining flat area of the site. It seems likely that the smaller passage tombs had been damaged by this time, as some of the stones from these tombs were used to construct houses and souterrains for the new open settlement. No evidence was found of external protection for this settlement area.

Knowth remained in the hands of the descendants of the Síl nÁedo Sláine to the eleventh century, but by then the kingdom of North Brega was in decline and its territorial extent diminished as the overlordship of the Ua Ruairc of Bréifne extended into Meath and the political power of the Ua Ruairc grew. Intensive settlement occurred on and around the mound of the main tomb at Knowth from the late-twelfth to the sixteenth century, and this settlement can be viewed as part of the wider changes that were taking place within Northern Brega at the time. When members of the Cistercian order arrived from France, they chose Mellifont, near Knowth, to establish their first monastery in 1142.

Knowth was granted to the Cistercians in 1157, probably by Tigernán Ua Ruairc. Furthermore, it seems that Knowth was used by the Anglo-Normans during the conquest of Meath: sometime around 1176, it seems that Richard Fleming, a vassal of Hugh de Lacy, intended to use the tumulus of the main tomb as a motte. Among the archaeological features dating to this period at Knowth are a bastion, an enclosed-courtyard farm, architectural fragments from a possible church and corn-drying kilns and ovens. In fact, Knowth has produced the richest assemblage of material of tenth- to thirteenth-century date from any rural site in Ireland, surpassed only by the urban excavations at Dublin and Waterford.

Examination of the Knowth finds for the tenth to twelfth centuries reveals much that is comparable to the wealth of archaeological material recovered from Viking-era Dublin, and numismatic finds in particular seem to indicate two main periods of contact and influence between the two sites - the first half of the tenth century and the later eleventh to twelfth centuries. There are some mid-tenth century Anglo- Saxon pennies and one early-eleventh century penny from the reign of Cnut, and there are also eight mid-twelfth century bracteates (coins struck on one side only) of Irish origin that seem to reflect the main period of trade and influence contact with Viking Dublin. Other finds from Knowth that find ready comparisons in Dublin include metal and bone stick-pins and ringed-pins and combs. One incomparable find from Knowth, however, is the ceremonial macehead recovered in the chamber of the eastern tomb in September 1982. This intricately carved item, which again appears to represent a face, was probably deposited as a dedicatory offering. It was found (by Liam O'Connor) at the entrance to the recess within the eastern tomb chamber that also housed the carved stone basin.

Speaking

at the Knowth 50th anniversary celebrations on 20 June this year, Mr O'Connor

described how, when he began to uncover the macehead from underneath a layer of shale, 'I

thought it was a modern thing, it seemed like it was made of plastic or polythene or something'.

The macehead was in fact carved from a piece of flint and is approximately 5,000 years old. It is ovoid in shape,

79mm long and weighs just over 324.5g. There is a perforation (17mm in diameter) through the narrower

end, suggesting it may have been mounted on a staff. The macehead has six sides; the two through which it

is perforated are flat, but the other two and the top and bottom are convex. Flint is a hard stone that is

difficult to work with, suggesting that the individual or individuals who carved the macehead were highly skilled craftspeople.

Speaking

at the Knowth 50th anniversary celebrations on 20 June this year, Mr O'Connor

described how, when he began to uncover the macehead from underneath a layer of shale, 'I

thought it was a modern thing, it seemed like it was made of plastic or polythene or something'.

The macehead was in fact carved from a piece of flint and is approximately 5,000 years old. It is ovoid in shape,

79mm long and weighs just over 324.5g. There is a perforation (17mm in diameter) through the narrower

end, suggesting it may have been mounted on a staff. The macehead has six sides; the two through which it

is perforated are flat, but the other two and the top and bottom are convex. Flint is a hard stone that is

difficult to work with, suggesting that the individual or individuals who carved the macehead were highly skilled craftspeople.

Part of a pestle macehead was found in the western tomb at Knowth in July 1967, at a central point in the tomb chamber; the remains of this item measured 38mm in length. At the time the flint macehead was recovered in 1982, these two from Knowth were the only maceheads to have been found as grave goods in an Irish passage tomb. 'Pestle maceheads were common to both Britain and Ireland but it was not the general practice to place these as grave offerings. The superb finish and design indicates that the Knowth maceheads were prestige items used by special people possibly on special occasions.'

Knowth was and continues to be a very special place. Generations of archaeology students and others have worked there to help bring its secrets to light. Speaking at the 50th anniversary, George Eogan suggested 'I would like to think that not only did they all receive valuable archaeological experience at Knowth, but also had a lot of fun in the process!' Whereas the major programme of excavation of the passage tombs may have finished, important work still goes on, not only in terms of publishing the outcome of the excavations, but also at the site itself.

The Office of Public Works has an ongoing project to work on Knowth House and its farm buildings; Meath County Council and the Discovery Programme have undertaken a LiDAR survey of the entire Knowth site; and as recently as late 2011 non-invasive electrical resistivity and geophysical surveying was undertaken by Joe Fenwick of the Brugh na Bóinne Research Project, School of Geography and Archaeology, NUI Galway, on part of the site just to the south-east of the main passage tomb. This has revealed hitherto unknown features, a rectangular-shaped ditched earthwork and a multiple-ring enclosure. While Joe Fenwick offers suggestions as to what these features might be, he rightly concludes 'the overall archaeological interpretation of Area 11 at Knowth should not be considered the final word in our understanding of the sub-surface features, as these have been revealed through geophysical means alone, a number of strategically placed excavation cuttings, for the purposes of obtaining dating evidence or for establishing stratigraphical chronologies, are to be recommended'.

Knowth continues to fascinate and inspire. Over the course of its illustrious existence it has evolved through many incarnations: from ancestral burial ground, to royal residence of North Brega, site of Anglo-Norman and Cistercian habitation, post-medieval settlement cluster, and nineteenth-century farmstead, to National Monument and part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There is much scope for future generations of archaeologists to seek for what Knowth has yet to reveal and to explore in greater detail, and in new ways, elements of the vast amount of data and material already uncovered. What has been discovered there to date, and what continues to emerge, will surely inspire the archaeological community and the general public alike to continue to appreciate and celebrate this extraordinary place.

Helena King - Irish Archaeological Research 2012

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Visitor Centre

| Tours

| Winter Solstice

| Solstice Lottery

| Images

| Local Area

| News

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Articles

| Art

| Books

| Directions

| Accommodation

| Contact