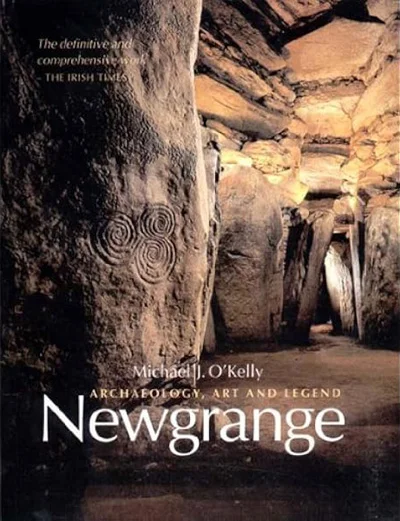

Newgrange – Archaeology, Art and Legend

Newgrange – Archaeology, Art and Legend

by Professor Michael J. O’Kelly and Claire O’Kelly is the definitive archaeological study of Newgrange and one of the most important works ever published on an Irish prehistoric monument.

Newgrange – Archaeology, Art and Legend

by Professor Michael J. O’Kelly and Claire O’Kelly is the definitive archaeological study of Newgrange and one of the most important works ever published on an Irish prehistoric monument.

The book presents the full results of the major excavation programme carried out at Newgrange by Professor Michael J. O’Kelly between 1962 and 1975, work that fundamentally transformed understanding of the monument’s construction, chronology, art, and astronomical alignment.

Drawing on detailed excavation records, architectural analysis, and comparative research, O’Kelly documents every stage of the investigation, interpretation, and restoration of the great passage tomb. The volume is richly illustrated and includes important contributions from Claire O’Kelly, who collaborated closely in the research and recording of the site from the earliest seasons of excavation at Newgrange.

First published in hardback in 1982, with a paperback edition following in 1988, the book remains essential reading for anyone seeking a serious understanding of the archaeology, megalithic art, and wider cultural significance of Newgrange within the prehistoric Boyne Valley.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Inside the book

When Professor Michael J. O’Kelly began excavations at Newgrange in 1962, the great mound was already one of Ireland’s best known ancient monuments. Yet much of what we now take for granted about its age, construction, and meaning was still uncertain. Newgrange - Archaeology, Art and Legend shows how more than a decade of careful excavation and analysis turned that uncertainty into one of the most detailed archaeological studies ever produced for a prehistoric site in Ireland.

The book begins by placing Newgrange in context. Early antiquarian accounts are considered alongside the site’s place in Irish tradition and literature, showing how ideas about the monument shifted over time, from speculation and folklore to more systematic investigation. O’Kelly also outlines how Newgrange came into State care and how that influenced the way the site was studied, protected, and eventually presented to the public.

The core of the volume is the excavation story itself. O’Kelly describes the methods used across the seasons from 1962 to 1975, including the work around the cairn slip and the careful exposure of features at the base of the mound. A key theme is how the cairn, kerb, and the great enclosing circle relate to each other, with Newgrange revealed as a planned composition rather than a single isolated structure.

The passage and chamber take centre stage, with detailed discussion of the architecture and the complex roofing system. One of the most important discoveries was the roof-box above the entrance, which enabled the recognition of the midwinter sunrise alignment. O’Kelly argues that this was not accidental, but a deliberate and successful attempt to incorporate the rising sun at midwinter into the design and use of the monument.

After excavation, the book turns to conservation and restoration, explaining the reasoning behind the stabilisation work and the rebuilding of elements of the mound. These chapters are especially valuable because they show the practical and ethical decisions involved when an excavated monument is not only recorded, but also conserved and presented for visitors.

In the discussion chapters, Newgrange is examined as a funerary and ritual monument, with attention to burial evidence, symbolism, and the wider landscape setting. Radiocarbon dating is used to establish a firm chronology, placing Newgrange in the earlier part of the fourth millennium BC and confirming that it is centuries older than Stonehenge and the pyramids of Egypt.

A major contribution of the book is its treatment of megalithic art. The carving techniques are described, along with the placement of decorated stones throughout the monument. Newgrange is also set within the wider tradition of Irish passage tomb art, underlining the importance of the Boyne Valley as a centre of Neolithic ceremonial life.

Finally, the appendices bring together specialist reports on artefacts, human remains, animal bone, plant remains, environmental evidence, and radiocarbon determinations. These technical studies support the interpretations in the main text and make the volume an essential reference for anyone researching Newgrange in depth.

Foreword by Colin Renfrew

Newgrange is unhesitatingly regarded by the prehistorian as the great national monument of Ireland; in the words of the late Seán Ó Ríordáin, 'one of the most important ancient places in Europe'. Its special importance has been widely realized since the early description by Edward Lhwyd in 1699, and each generation finds in it something new and interesting. The widespread realization in recent years that the very early 'megalithic' architecture of western Europe is something notably and essentially European, owing little or nothing to the Near East, has only served to heighten our admiration for some of these great and early constructions, of which Newgrange is undoubtedly one of the very finest.

Our own generation has been particularly fortunate that, since 1962, this important site has been the subject of investigation by Professor O'Kelly, ably assisted by his wife Claire. To them we are indebted for a number of important discoveries and conclusions which are set out in full here. Indeed in the face of so much new information, it is interesting to look back to the pessimism which prevailed nearly two centuries ago, to the gloomy view that very little could ever be known about it. In his Tour in Ireland, published in 1807, the distinguished English antiquary, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, wrote of Newgrange:

I shall not unnecessarily trespass upon the time and patience of my readers in endeavouring to ascertain what tribes first peopled this country, nor to what nation the construction of this singular monument may reasonably be attributed for, I fear, both its authors and its original destination will ever remain unknown. Conjecture may wonder over its wild and spacious domains but will never bring home with it either truth or conviction. Alike will the histories of those stupendous temples at Avebury and Stonehenge which grace my native country, remain involved in obscurity and oblivion.

Now we know so very much more. In the first place, as reported here, the mound and its contents have been reliably dated. The 'uncorrected' radiocarbon date of around 2500 bc must be the equivalent, after the calibration of the radiocarbon time scale (using the corrections afforded by tree-ring dating), of a date in calendar years of about 3200 BC. There can be no doubt, therefore, that Newgrange is older than Stonehenge, older than Avebury, and indeed older by several centuries than the pyramids of Egypt.

This early construction highlights still further the great fascination of the carved stone decoration of the Boyne tombs, and of Newgrange itself. Mrs O'Kelly's corpus of the art from this site makes an important contribution here. The precise purpose of this decoration is still a matter for discussion, and great interest was aroused by Professor O'Kelly's discovery that some of the stones were decorated on surfaces which could never have been visible to the visitor to the tomb: their secret was revealed only in the course of excavation and restoration work. Here the case is convincingly argued that these stones were not re-used from some earlier monument. Moreover the care with which the construction was planned and executed does not support the view that these carved surfaces were obscured by accident or by the incompetence of the builders. Was this hidden carving then the consequence of some secret piety of its makers, invisible to mortal eyes, but present nonetheless for eternity?

The most remarkable discovery reported here came about unexpectedly in 1963, when the investigation of a seemingly anomalous slab led to the recognition of the 'roof-box', a carefully constructed aperture above the entrance. It is so situated that at midwinter's day the rays of the rising sun penetrate the full length of the entrance passage, and reach into the chamber itself. Whatever one's scepticism for some of the claims made on behalf of 'megalithic astronomy' or of 'astroarchaeology', it is difficult not to see this as a deliberate and successful attempt to incorporate the midwinter sunrise as a significant element in the planning and use of the monument. This arrangement constitutes one of the very earliest astronomical, or rather solar, alignments ever recorded, earlier by far than those of Stonehenge and the other British stone circles and standing stones. It still works today, despite the small changes over the millennia in the earth's position relative to the sun, and according to Professor O'Kelly will continue to do so as long as Newgrange continues to stand.

This volume constitutes the final and definitive report of these excavations and researches, with studies by a number of specialists given as appendices. But it has turned into something very much more than simply an excavation report: into a review of the history of research at Newgrange, a survey of its place in prehistory, and a corpus of the remarkable carvings which embellish the stones of this 'cathedral of the megalithic religion'.

As discussed in chapter 12, former generations held that Newgrange, and those other great monuments of the Boyne Valley, Knowth and Dowth, were the work of colonist-builders, representing the end of a line of devolution which had begun in the Mediterranean world, starting perhaps with the impressive stone tombs of Mycenae. Now we know that it is older by far than these Aegean comparisons, and that Newgrange is not the work of immigrants already greatly skilled in architecture, but instead the product of a more local evolution, from simple to complex. Some at least of the questions so pessimistically posed in 1807 by Colt Hoare can now be answered, and we can instead share the view of another early antiquary, George Petrie, and, on the basis of the careful researches reported here, with him agree 'to allow the ancient Irish the honour of erecting a work of such vast labour and grandeur'.

Colin Renfrew

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk